What this guide covers

This guide explains the concept, meanings, synonyms, and real‑world impact of imposter thoughts; maps seven recognizable patterns; and provides a five‑step plan grounded in CBT‑style tools and current clinical summaries for measurable progress over time. Leading 2025 explainers emphasize that practical definitions, simple language, and stepwise help improve satisfaction and trust in mental‑health articles.

Quick definition and meaning

In plain terms, imposter syndrome is a pattern of persistent self‑doubt where successes are dismissed and there is a fear of being “exposed” as a fraud despite objective evidence of competence. Major guides note it is not a formal DSM diagnosis but a well‑documented behavioral pattern affecting work, school, and personal life across demographics. Common alternates include impostor phenomenon, impostorism, perceived fraudulence, and “fraud syndrome,” reflecting how widely the idea is discussed beyond clinical manuals.

One‑sentence glossary (search intent variants)

- “Imposter syndrome meaning”: a tendency to disbelieve earned success and fear exposure as a fraud, even with proof of ability.

- “Impostor syndrome meaning”: same intent; variant spelling used globally for the same phenomenon in non‑technical contexts.

- “Meaning imposter syndrome”: shorthand for definition queries that seek a clear, everyday explanation.

- “Imposter syndrome definition”: a short description of the chronic self‑doubt and non‑internalization of success that typifies the experience.

- “Define impostor syndrome”: the formal ask to label the phenomenon known for the impostor cycle, perfectionism, and fear of exposure.

Why it happens (the big drivers)

Clinical and consumer summaries converge on overlapping drivers: perfectionistic standards, high‑stakes or evaluative environments, identity stressors/representation gaps, and difficulty internalizing positive feedback. Social comparison, inconsistent early feedback, and fast‑moving roles can reinforce negative self‑appraisals that maintain the “fraud” narrative even after major milestones. These pressures feed a well‑described loop called the imposter cycle, which makes doubts feel “true” regardless of facts.

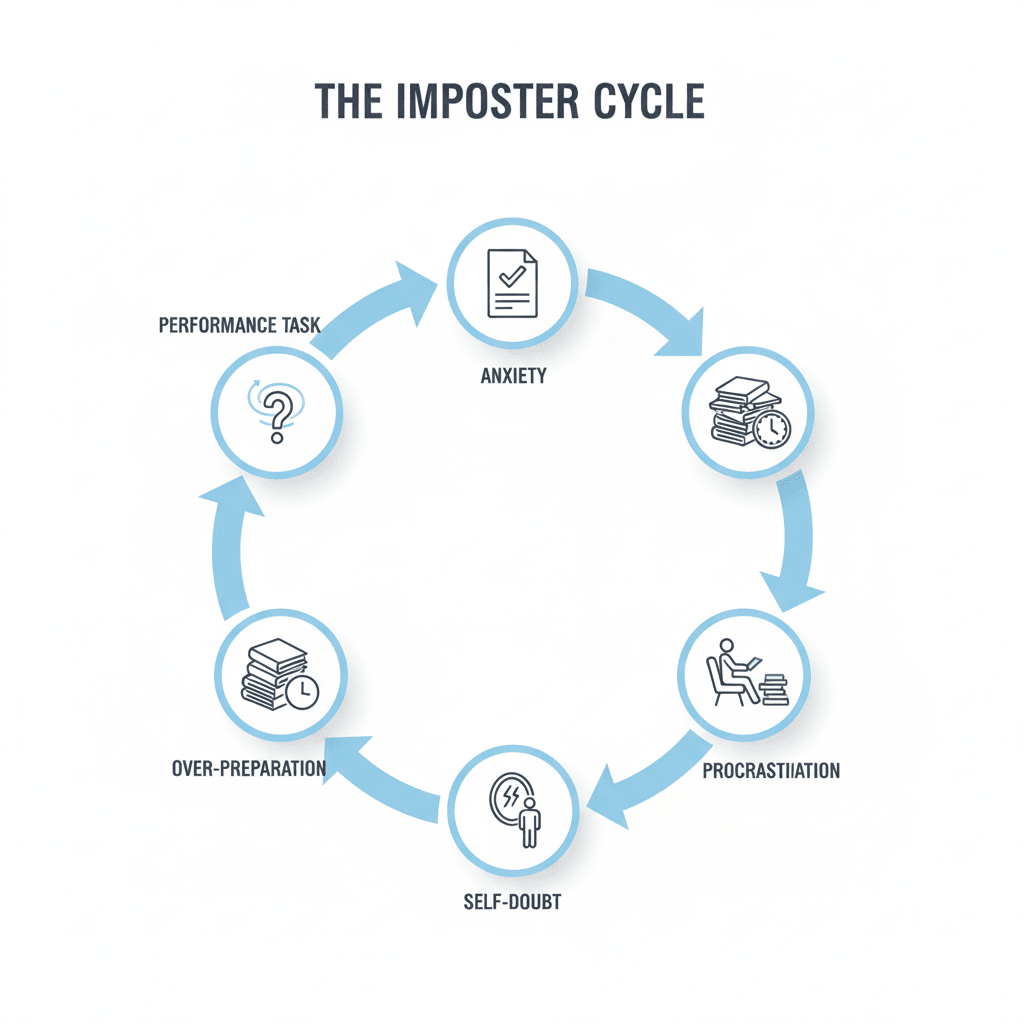

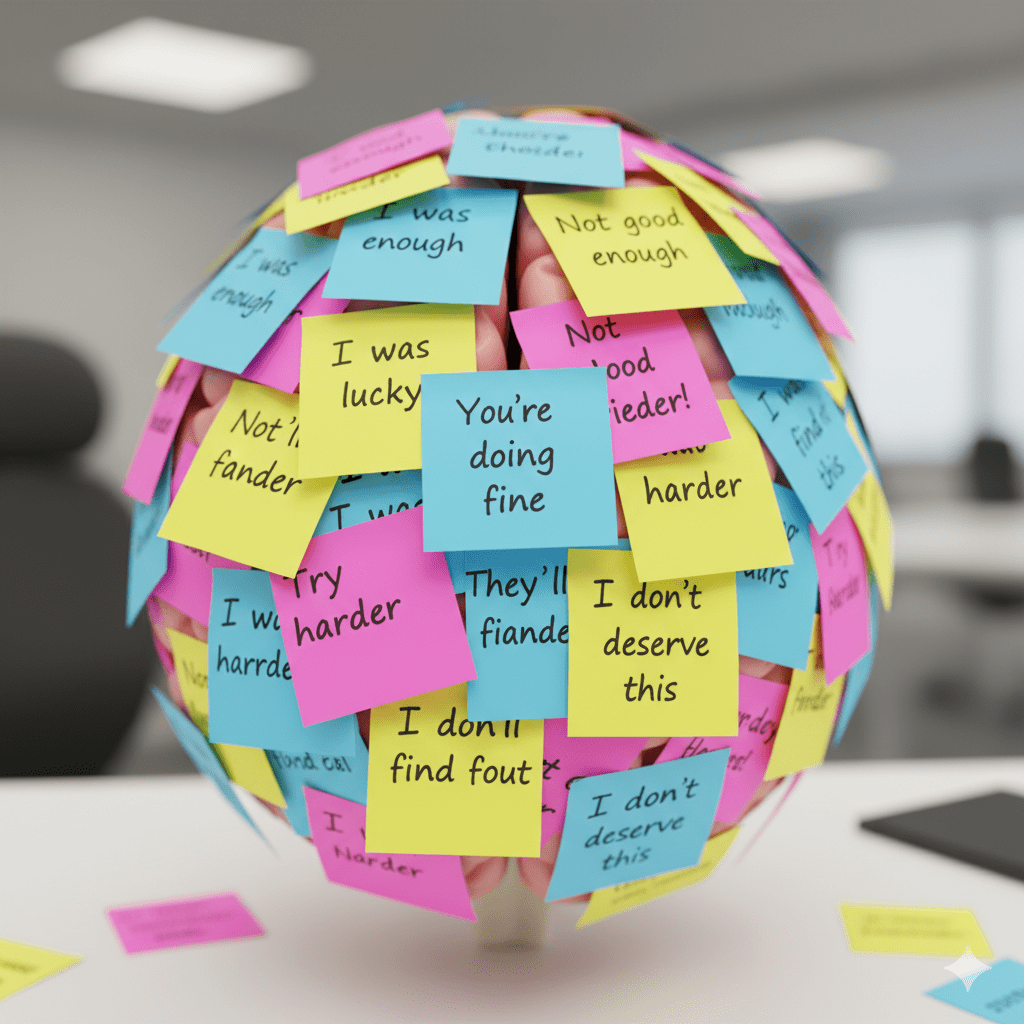

The imposter cycle (why doubts keep returning)

The cycle typically begins with a performance task, triggers anxiety, and splits into over‑preparation or procrastination, both of which briefly relieve anxiety but then reset doubts for the next task. Over‑preparers assume success came only from excessive effort, whereas procrastinators assume last‑minute success was “luck,” and both explanations block internalizing competence. Recognizing the cycle is a practical first step to change, because it clarifies exactly which behaviors to adjust in the short term.

1) The Perfectionist

Defining belief: “If it isn’t flawless, it’s failure,” which raises shame after minor errors and makes healthy standards feel unsafe. Typical signs include over‑editing, postponing launches, and rejecting praise with alternative explanations that minimize skill. The practical aim is to ship to a “good‑enough” spec and measure outcomes rather than polishing indefinitely.

2) The Expert

Defining belief: “If I don’t know everything, I know nothing,” keeping learning in the shadows and launches on hold until there is “total mastery”. Typical signs include chasing endless credentials and delaying visibility on projects that are already valuable. Publishing with a clear scope and adding iterative updates reduces avoidance while sustaining quality growth.

3) The Natural Genius

Defining belief: “If I were truly capable, it would be easy,” which pathologizes normal effort and learning curves. Signs include dropping skills quickly after early mistakes and interpreting practice as proof of inadequacy. Reframing “effort as evidence of growth” plus deliberate practice improves tolerance for the middle of the curve.

4) The Soloist

Defining belief: “If I need help, I’m not competent,” isolating people from mentoring, feedback, and healthy delegation. Signs include taking on too much alone and hiding uncertainty to avoid “exposure,” which worsens overload. One weekly, intentional ask for help or a small delegation can reset collaboration as a competence move, not a weakness.

5) The Superhero

Defining belief: “If I’m not excelling everywhere, I’m failing,” which converts over‑commitment into a worthiness test. Signs include saying yes to everything and equating exhaustion with inadequacy rather than workload or boundaries. Capping commitments and scheduling renewal time breaks the “more equals worthy” equation and protects performance quality.

6) The Over‑Preparer

Cycle‑based pattern: Excess effort is used to create safety, then success is attributed to that surplus instead of skill, keeping the “fraud” story intact. Signs include “study to the last minute” for routine tasks and difficulty trusting past competence as a predictor of future success. Timeboxing prep and shipping on schedule retrain the brain to link outcomes to skill and process, not sheer volume.

7) The Procrastinator

Cycle‑based pattern: Delay preserves “plausible deniability” and ensures rushed work “proves” the competence story wrong in the next review. Signs include last‑minute bursts, avoidance of feedback, and interpreting adrenaline as a talent shortage rather than a timing issue. Tiny “starter reps” plus deadlines convert avoidance into momentum and reduce catastrophic predictions over repeats.

Real‑life examples (work, school, creative)

- New team lead discounts a promotion as “luck,” avoids feedback, and over‑works off‑hours to stay invisible; this maps to perfectionist and superhero patterns within the imposter cycle.

- High‑performing student encounters first setbacks, label them proof of fraudulence, and opts out of seminars; this is a classic cycle entry that responds to graded exposure plus reframes.

- Designer delays portfolio updates “until perfect,” then posts late with an apology; shipping to pre‑set “good‑enough” criteria counters this loop effectively.

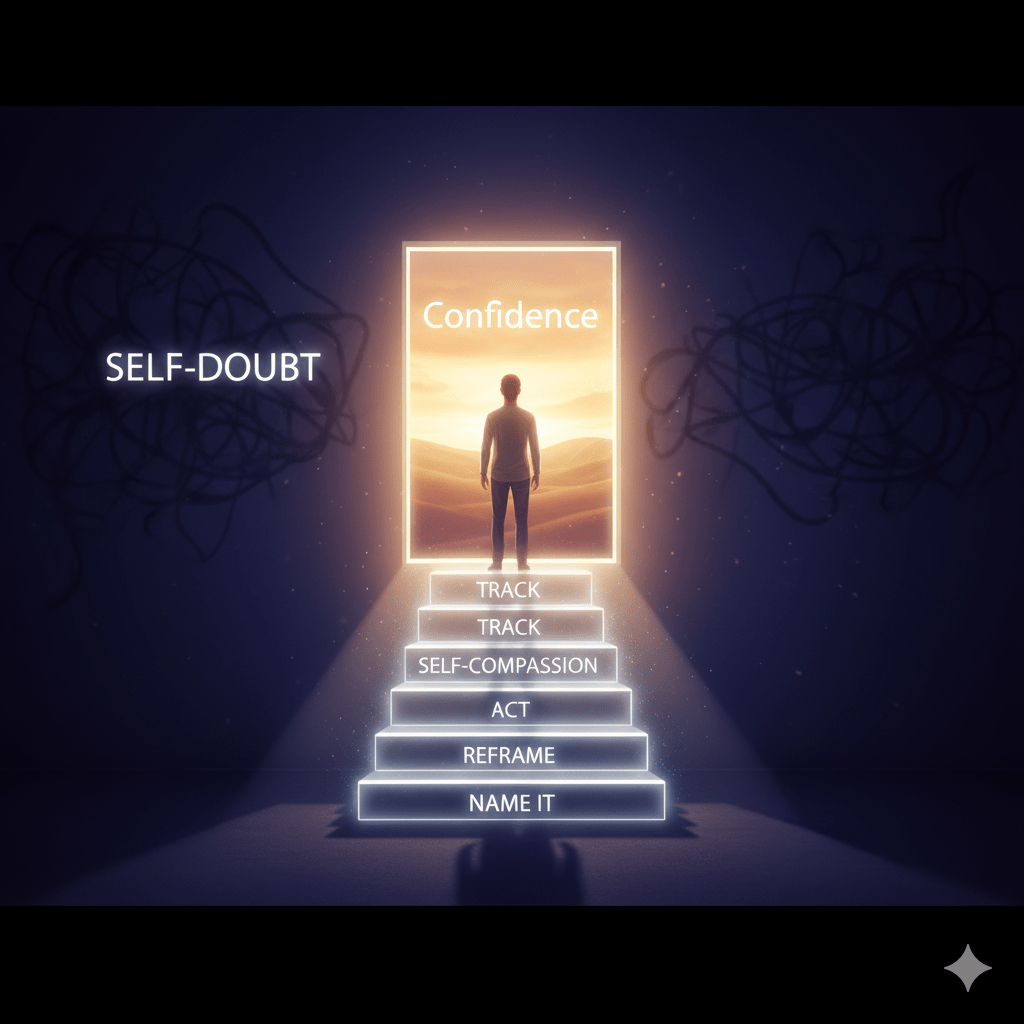

5‑Step Fix (practical, repeatable, evidence‑informed)

- Name the pattern

Label the current pattern (Perfectionist, Expert, Natural Genius, Soloist, Superhero, Over‑Preparer, Procrastinator) to reduce fusion with thoughts and choose precise counter‑moves. Naming turns global self‑judgments into targeted skill steps that are easier to practice and track.

- Evidence log + cognitive reframe

Keep a rolling log of wins, process evidence, and third‑party feedback, then run short cognitive restructuring prompts to test negative predictions against facts. Reframing questions such as “What skill did I apply?” and “What neutral evidence contradicts this belief?” creates quick corrective experiences.

- Behavioral experiments and graded exposure

Pick a small “stretch but safe” task, write a prediction, act, and compare predicted vs actual to recalibrate threat estimates over time. Repeated small wins weaken catastrophic thinking and reduce avoidance without requiring perfect confidence first.

- Self‑compassion scripts + values alignment

Swap punitive self‑talk for brief compassionate phrases that normalize learning, then tie actions to chosen values (service, creativity, impact) to judge progress by alignment, not flawlessness. Values‑anchoring helps motivation survive mistakes, which are inevitable in growth.

- Track and get support

Use a brief self‑check like the Clance Impostor Phenomenon Scale (CIPS) to notice trends (not to diagnose), and pair with a mentor or peer to review logs weekly for consistency. Accountability reduces isolation, improves follow‑through, and shortens the learning cycle.

Evidence snapshot: what helps most

- CBT techniques—cognitive restructuring, behavioral experiments, and graded exposure—consistently show benefit for imposter‑related distress and functioning.

- Early studies and recent student samples suggest CBT can improve mental health, self‑esteem, and emotion regulation among those reporting strong impostor feelings.

- Leading consumer and clinical guides converge on skills over labels: name the pattern, test predictions, and collect real‑world data to internalize competence.

Treatment, not “cure” (clear, responsible guidance)

- Articles sometimes ask for treatment for imposter syndrome or even “curing imposter syndrome,” but experts frame it as a modifiable pattern rather than a disorder with a one‑time cure.

- Practical “treatment” includes CBT‑style skills, mindfulness, social support, and environment changes, with worksheets and short scripts making habits easier to sustain.

- Health sources emphasize that significant anxiety, depression, or impairment warrants professional support alongside self‑help, and progress typically comes from repeated, small wins.

At work, school, and beyond: what to watch

- Workplace guides flag promotions, high visibility, and evaluative cultures as common triggers, making proactive coping (timeboxing, feedback, delegation) especially important on new teams.

- Academic and professional transitions heighten risk due to constant comparison and public metrics, but small experiments and data‑driven logs quickly improve calibration.

- Consumer explainers advise separating normal growth discomfort from “I am a fraud” narratives to keep learning on track without over‑personalizing mistakes.

Conclusion

Imposter feelings are common, but the pattern is changeable: define the moment, collect evidence, run small experiments, practice compassion, and add support to shrink doubt and internalize success over time. Responsible sources frame imposterism as a skills problem, not a personal defect, and CBT‑style tools remain the most practical path to durable gains in confidence and performance.

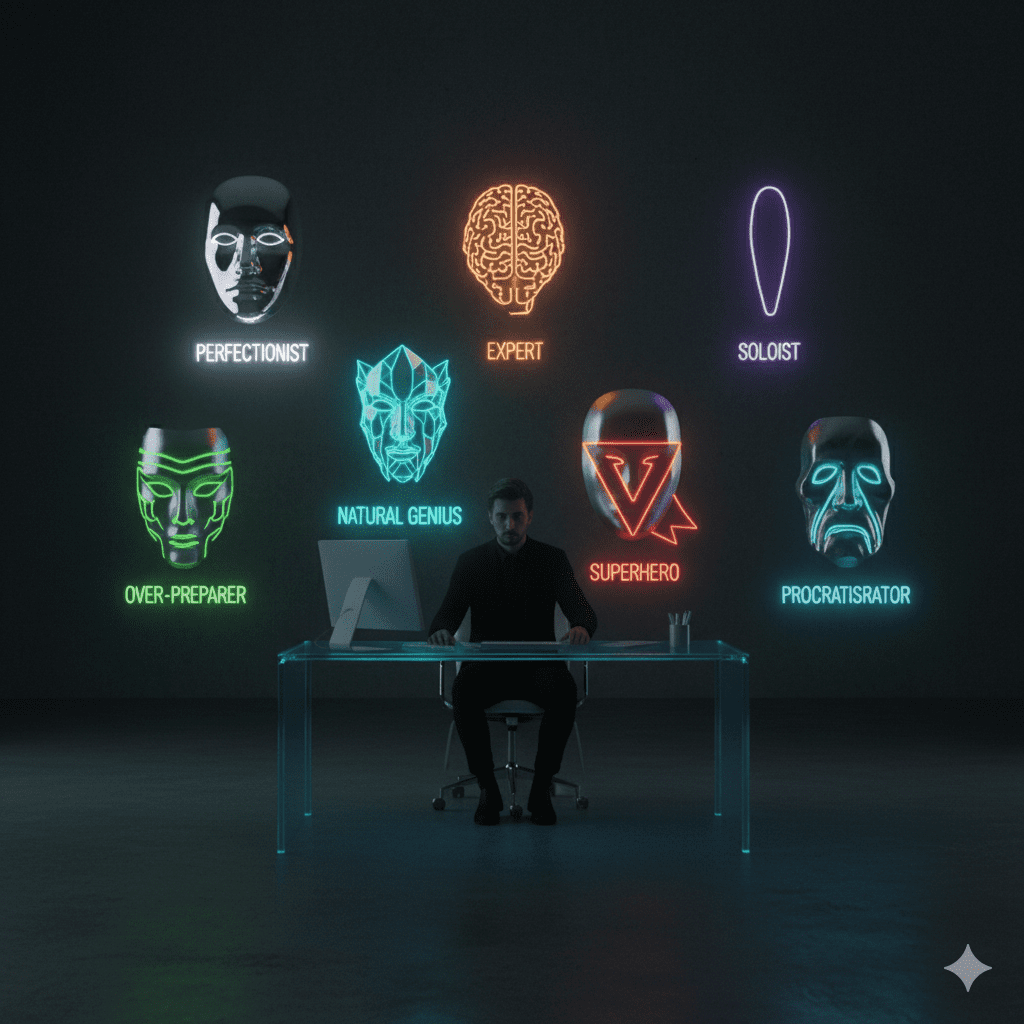

What are the 7 types of impostor syndrome?

Common patterns include Perfectionist, Expert, Natural Genius, Soloist, Superhero, Over‑Preparer, and Procrastinator.

Is impostor syndrome a mental health disorder?

No, it’s a cognitive‑behavioral pattern that often overlaps with anxiety, perfectionism, and burnout and responds to skills‑based strategies.

What causes impostor syndrome?

High standards, comparison, high‑stakes environments, under‑representation, and difficulty internalizing praise can all contribute.

How do I overcome impostor syndrome quickly?

Start an evidence log, use brief cognitive reframes, and run small behavioral experiments with timeboxing to ship work on schedule.

What is the Clance Impostor Phenomenon Scale (CIPS)?

CIPS is a self‑assessment tool to track impostor‑type thoughts over time; it is not a diagnostic test.

Does therapy help?

CBT‑style tools—cognitive restructuring, exposure, and self‑compassion—are commonly recommended and can be paired with mentoring or coaching.

How long does improvement take?

Consistency matters; many people notice progress over weeks by repeating small experiments and reviewing evidence logs with accountability.